Our enemies are proliferating, so we must adapt

On June 18, 1935, the United Kingdom and Germany entered “a permanent and definite agreement” that limited Germany’s total warship tonnage to 35 percent of the British Commonwealth’s. This was a major concession from Great Britain, since agreements at the Washington (1921–22) and London (1930) naval conferences had already significantly reduced its own fleet. Hitler defined “permanent and definite” to mean lasting less than four years: He abrogated the treaty on April 28, 1939, four convenient months before the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact carved up Poland and started World War II. Arms control at work.

After 1945, America concluded a series of treaties that were, when signed or shortly thereafter, almost uniformly disadvantageous to us. Considerable efforts to eliminate these restraints have been made, but significant risk remains of reverting to the old ways or not extracting ourselves from the remaining harmful treaties. Whoever next wins the presidency should seek the effective end of the usual arms-control theology before the tide turns again.

To have any chance of bolstering U.S. national security, arms control must fit into larger strategic frameworks, which it has not done well in the last century. Even if they made sense in their day, many arms-control treaties have not withstood changing circumstances. Preserving them is even less viable as we enter a new phase of international affairs: the era after the post–Cold War era. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Iran’s ongoing “ring of fire” strategy against Israel, China’s aspirations for regional and then global hegemony, and the Beijing–Moscow axis augur trying times. We need a post–post–Cold War strategy avowedly skeptical of both the theoretical and the operational aspects of the usual approaches to arms control.

Rethinking arms-control doctrine down to its foundations began with Ronald Reagan’s 1983 Strategic Defense Initiative and resumed with George W. Bush. The partisan and philosophical debates they launched have continued ever since, but the next president will confront foreign- and defense-policy decisions that cannot be postponed or ignored. Best to do some advance thinking now.

Bush’s aspirations were more limited than what liberals derided as Reagan’s “Star Wars.” Bush worried about American vulnerability to the prospect of “handfuls, not hundreds,” of ballistic missiles launched against us by rogue states. Providing even limited national missile defense, however, required withdrawing from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, as Bush did in December 2001. Arms control’s high priests and priestesses, and key senators such as Joe Biden and John Kerry, were apoplectic. Missile defense was provocative, they said. Leaving the ABM Treaty meant abandoning “the cornerstone of international strategic stability” (a phrase commonly used by politicians, diplomats, and arms controllers) and upsetting the premise of mutual assured destruction, they said.

But Bush persisted and withdrew. As the saying goes, the dogs barked and the caravan moved on. In 2002, Bush turned to a new kind of strategic-arms agreement with Vladimir Putin, the Treaty of Moscow, which set asymmetric limits on deployed strategic nuclear warheads and was structured in ways very different from earlier or later nuclear-weapons treaties. We abandoned the complex, highly dubious counting and attribution metrics of prior strategic-weapons deals, as well as verification procedures that Russia had perfected means to evade. The Treaty of Moscow was sufficiently reviled by the arms-control theocracy that Barack Obama replaced it in 2010 with the New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), reverting to failed earlier approaches, more on which below.

During Bush’s first term, we also blocked efforts in the United Nations at international gun control. We established the G-8 Global Partnership — to increase funding for the destruction of Russia’s “excess” nuclear and chemical weapons and delivery systems — and launched the Proliferation Security Initiative to combat international trafficking in weapons and materials of mass destruction. Neither effort required treaties or international bureaucracies. We unsigned the Rome Statute, the treaty that had created the International Criminal Court, to protect U.S. service members from the threat of criminal action by unaccountable global prosecutors.

Finally, the Bush administration scotched a proposed “verification” protocol to the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) that risked intellectual-property piracy against U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturers but did not enhance the verification of breaches. The BWC and the Chemical Weapons Convention express aspirations not to use these weapons of mass destruction, but it is almost impossible to verify compliance with them. Moreover, arms controllers forget that the BWC sprang from Richard Nixon’s unilateral decision to eliminate American biological munitions, which proved that we could abjure undesirable weapons systems on our own.

The Bush administration went a long way toward ending arms control, but the true believers returned to power under Obama. Eager to ditch the heretical Treaty of Moscow, his negotiators produced New START — the lineal descendant of two earlier SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) and three START agreements — which entered into force in February 2011 for ten years, extendable once for five more. The Senate should never have ratified this execrable deal, as I explained in these pages (“A Treaty for Utopia,” May 2010). Nonetheless, with a Democratic majority it did so in a late-2010 lame-duck session, by 71 votes (all 56 Democrats, two independents, and 13 Republicans) to 26. While the vote seems lopsided, there were three nonvoters — retiring anti-treaty Republicans who opposed ratification — and the Senate secured the constitutionally required two-thirds ratification majority by only five votes. Today, given a possible Republican majority ahead and the unlikelihood that so many Republicans would defect again, ratifying a successor treaty is a dubious prospect at best.

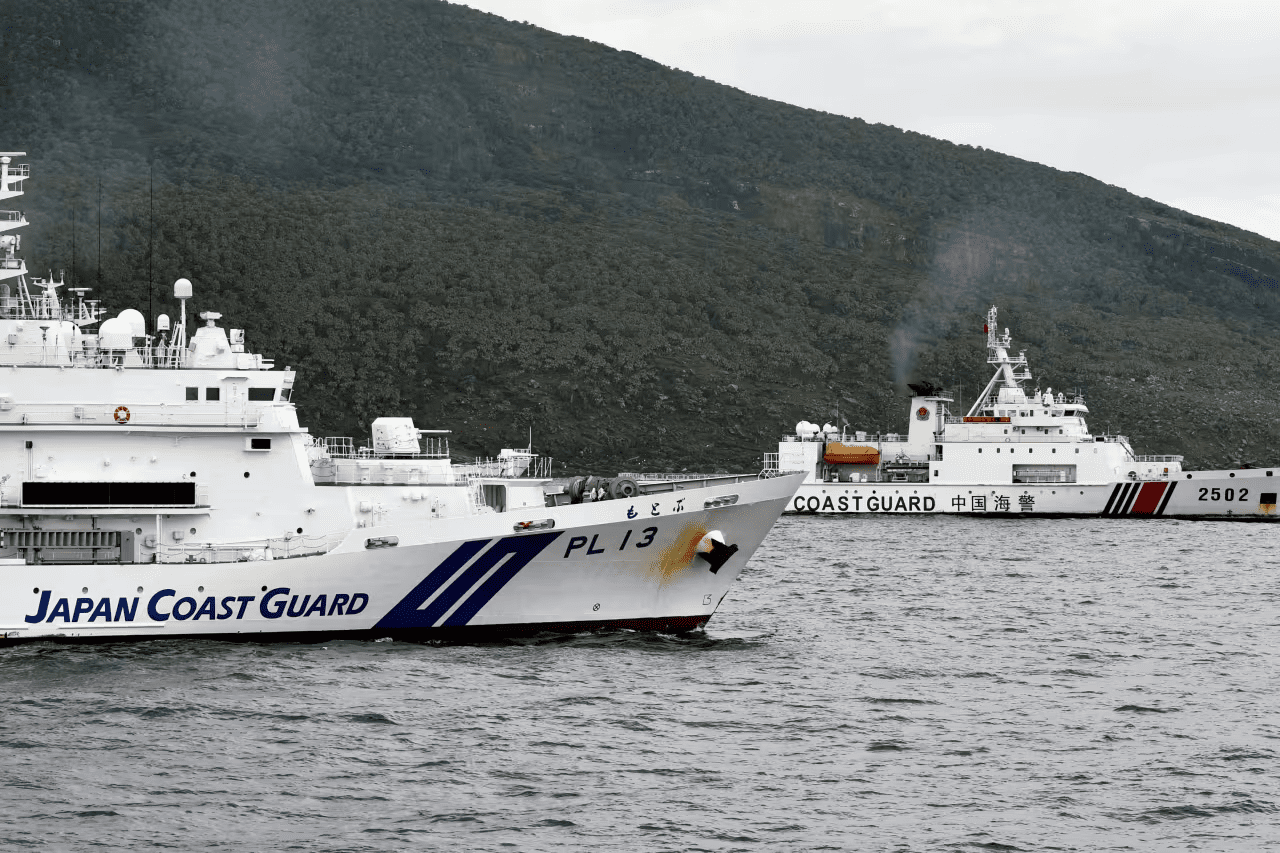

The Trump administration resumed untying Gulliver, exiting the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 2019. While the INF Treaty may have made sense in the 1980s, by the time of withdrawal only the United States was abiding by its provisions. The likes of China and Iran, not treaty parties, were accumulating substantial numbers of intermediate-range ballistic missiles, and Russia was systematically violating INF Treaty limits. That left America as the only country abiding by the treaty, an obviously self-inflicted handicap that withdrawal corrected. Then, in 2020, the U.S. withdrew from the Open Skies Treaty because Russia had abused its overflight privileges and because our national technical assets made overflight to obtain information obsolete. Russia subsequently withdrew from Open Skies.

But the arms-control theology still has powerful adherents. On January 26, 2021, newly inaugurated Joe Biden sent his first signal of weakness to Putin by unconditionally extending New START for five years without seeking modifications to it. This critical capitulation was utterly unwarranted by New START’s merits or by developments since its ratification. The treaty was fatally defective in that it did not address tactical nuclear weapons, in which Russia had clear superiority. It remains true that no new deal would be sensible for the United States unless it included tactical as well as strategic warheads.

In addition, technological threats that postdate New START (which deals with the Cold War triad of land-based ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and heavy bombers) need to be confronted, especially cruise missiles, which can now reach hypersonic speeds.

Most important, China has made substantial progress since 2010 toward becoming a peer nuclear power. Beijing may not yet have the deliverable-weapons capacity of Washington or Moscow, but the trajectory is clear.

A tripolar U.S.–Russian–Chinese nuclear world (no other power has or will have rates of warhead production comparable to China’s) would be almost inexpressibly more dangerous than a bipolar U.S.–USSR world. The most critical threat that China’s growing strategic-weapons arsenal poses is to the United States. How will it manifest? Will we face periodic, independent risks of nuclear conflict with either China or Russia? Or a combined threat simultaneously? Or serial threats? Or all of the above? Answers to these questions will dictate the nuclear-force levels necessary to deter first-strike launches by either Beijing or Moscow or by both, and to defeat them no matter how nuclear-conflict scenarios may unfold.

None of this is pleasant to contemplate, but, as Herman Kahn advised, thinking about the unthinkable is necessary in a nuclear world. These existential issues must be addressed before we can safely enter trilateral nuclear-arms-control negotiations. Beijing is refusing to negotiate until it achieves rough numerical parity with Washington and Moscow. There is little room for diplomacy anyway, since in February 2023 Russia suspended its participation in New START. Further strategic-weapons agreements with Russia alone would be suicidal: Bilateral nuclear treaties may be sensible in a bipolar nuclear world, but they make no sense in a tripolar world. Russia and China surely grasp this. We can only hope Joe Biden does as well. Next January, our president will have just one year to decide how to handle New START’s impending expiration. We should assess now which candidates understand the stakes and are likely to avoid being encumbered by agreements not just outmoded but dangerous for America.

A closely related challenge is the issue of U.S. nuclear testing. Unarguably, if we do not soon resume underground testing, the safety and reliability of our aging nuclear arsenal will be increasingly at risk, as America’s Strategic Posture, a recent congressionally mandated report, shows. Since 1992, Washington has faced a self-imposed ban on underground nuclear testing even though no international treaty in force prohibits it. The Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963 bars only atmospheric, space, and underwater testing, a gap that the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which would have banned all testing, was intended to close. Because, however, not all five legitimate nuclear powers under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) ratified the CTBT, it never entered into force and likely never will. Though the U.S. signed the CTBT in 1996, the Senate rejected its ratification by a vote of 51 to 48 in 1999. Russia recently announced its withdrawal, thereby predictably dismaying Biden’s advisers. The next U.S. president should extinguish the CTBT by unsigning it. As was recently revealed, Beijing seems to be reactivating and upgrading its Lop Nor nuclear-testing facility. We can predict confidently that neither China nor Russia will hesitate to do what it thinks necessary to advance its nuclear-weapons capabilities. We should not be caught short.

Additional unfinished business involves the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty, another arms-control “cornerstone,” this one of European security. Effective since 1990, as the Cold War ended, CFE became obsolete almost immediately. The Warsaw Pact disbanded (its members largely joining NATO) and the USSR fragmented. Russia suspended CFE Treaty compliance several times before withdrawing formally in November 2023, having already invaded Ukraine, another CFE Treaty party. In response, the United States and our NATO allies suspended CFE Treaty performance. Like the CTBT, the CFE Treaty is a zombie that the next president should promptly destroy.

The list of arms-control-diplomacy failures goes on. The NPT, for example, has never hindered truly determined proliferators such as North Korea (which now has a second illicit nuclear reactor online) or Iran, much as arms-control agreements have consistently failed to prevent grave violations by determined aggressors.

This long, sad history has given us adequate warning, and the next president should learn from it. The array of threats the United States faces makes it imperative that we initiate substantial, full-spectrum increases in our defense capabilities, from traditional combat arms and cyberspace assets to nuclear weapons. Instead of limiting our capabilities, we must ensure that we know what we need and have it on hand. We are nowhere near that point.

This article was first published in The National Review on January 25, 2024. Click here to read the original article.