The new administration should reject mandatory ‘assessments’ and fund only programs that work.

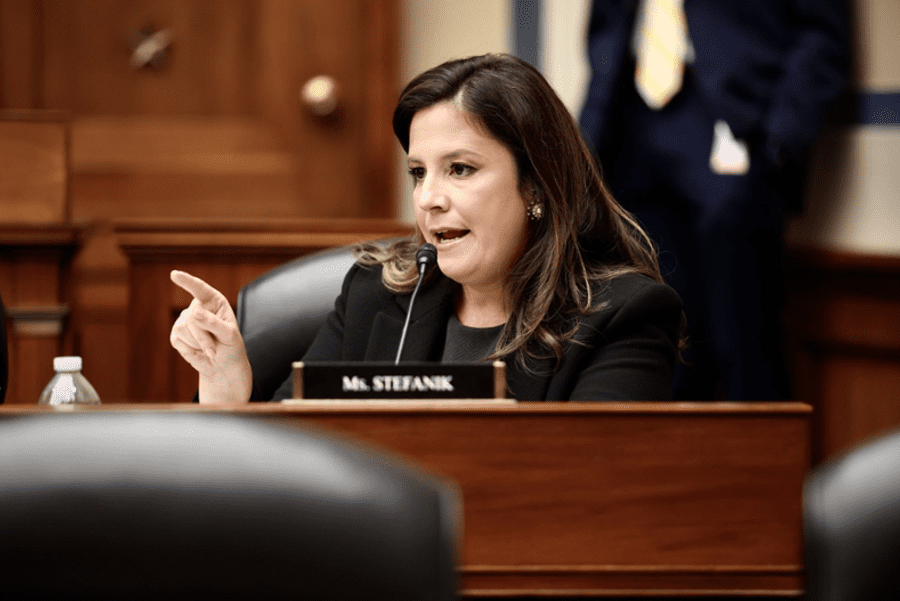

Elise Stefanik, Donald Trump’s nominee for U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, has her work cut out for her. Fortunately, she’s already aware of the U.N.’s flaws. In a September op-ed for the Washington Examiner, she applauded Mr. Trump for withdrawing from the “corrupt and antisemitic” Human Rights Council and defunding the U.N. Relief and Works Agency, the U.N.’s permanent refugee organization for Palestinians, during his first term. She also praised House Republicans for voting to impose sanctions on the International Criminal Court.

Ms. Stefanik joins a long line of U.S. officials dismayed by the U.N.’s profound failings, including its deep-seated bias against Israel. As one of those officials, my contributions to U.N. reform include implementing President George W. Bush’s decision to remove America’s signature from the treaty establishing the ICC, advising Mr. Bush to vote against creating the Human Rights Council and then casting the vote, and leading the effort to repeal the U.N.’s infamous “Zionism is racism” resolution. Years later, in 2018, I recommended that Mr. Trump withdraw from the Human Rights Council and defund Unrwa.

But the job is far from over. No one should underestimate the difficulties that lie ahead or the effort that will be required to achieve real, lasting U.N. reform. A major obstacle is our own State Department. Its bureaucracy historically has been unwilling to do the heavy lifting required to muster support for transforming the U.N. That burden will fall not only on U.S. missions to U.N. components but also on the State Department’s regional bureaus, which are responsible for bilateral relations with the other 192 members. For decades, the regional bureaus have found reasons not to engage, pleading that innumerable bilateral issues be given higher priority. Secretary of State-designate Marco Rubio will need to crack the whip for reform to succeed.

The new administration should prove to U.N. members that its goal of reform isn’t merely rhetorical. Washington’s most important weapon will be its wallet—decisions about how much it financially contributes, or doesn’t contribute, to the U.N. Current spending is out of control. In 2022, the most recent year for which we have accurate data, the U.S. contributed more than $18 billion, accounting for roughly one-third of total U.N. funding. As the Heritage Foundation reported, “the U.S. provided more funding to the U.N. system than 185 other U.N. member states combined.” That year we forked over 8.5 times the amount that China, the second-largest donor, contributed.

Funding for U.N. components falls into two categories: mandatory “assessed” contributions and voluntary contributions. Assessments are calculated by opaque “capacity to pay” formulas, which have historically made America the largest contributor. After decades of negotiation and legislation, U.S. assessments are capped at 22% for most contributions and 25% for peacekeeping operations. On a one-nation-one-vote basis, bodies like the General Assembly decide agency budgets, and members then pay their percentage shares.

Assessments therefore amount to taxation of America by other U.N. members. A majority of member governments tells us what we owe, on pain of losing our vote in U.N. governing bodies if we don’t pay up. That alone is sufficient reason to reject the concept of assessments, since it isn’t our votes in these bodies that matter. The only vote that matters is our Security Council vote (and veto), our main shield against one-nation-one-vote majorities U.N.-system-wide. Our permanent seat in the council and its vote are written into the U.N. Charter, and we can veto changes to the charter. The potential negative consequences of ending assessed contributions, then, are essentially nil.

U.N. bureaucrats, U.S. officials and nongovernmental organizations assert without evidence that America gets enormous credit for its contributions to the U.N. and warn that America’s influence would diminish worldwide if those contributions were significantly reduced or eliminated. These assertions are false. Special-interest advocates simply take our current level of funding for granted, complain that it’s inadequate and demand more. It’s time they get their comeuppance.

The U.N. Charter doesn’t require assessed contributions. The charter says merely that the organization’s expenses shall be “apportioned by the General Assembly,” but requires no specific approach. The assembly could make contributions entirely voluntary, as is the case already with some U.N. agencies and programs. The Trump administration simply needs to resolve against the U.N. system’s longstanding reliance on assessments until the totally voluntary approach prevails and other members acquiesce.

Shortly after taking office, Mr. Rubio and Ms. Stefanik should announce that the U.S. no longer accepts the concept of assessed contributions. Henceforth, we will pay only voluntary contributions, which we will decide by evaluating the performance of each U.N. agency and program. We may zero out some programs; we may voluntarily fund others at or near our current assessed level; we may even increase funding for others. But we will decide. And every other U.N. member will have the same prerogative.

This approach rests on the revolutionary assumption that we fund the U.N. based on its performance, paying only for what we want and insisting that we get what we pay for. U.N. agencies that are funded entirely by voluntary donations, such as the World Food Program, generally tend to outperform those funded by assessments. Because they have to prove their worth annually, they have an incentive to sustain and even boost their performance. If voluntarily funded programs fail or falter, we should reduce their funding accordingly.

Ultimately, some agencies will prove unreformable, and America should simply withdraw from them. The U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization immediately comes to mind, as it did for President Ronald Reagan, who withdrew the U.S. from Unesco in 1984. The country rejoined in 2003 under Mr. Bush, Mr. Trump withdrew in his turn, and Joe Biden rejoined. Doubtless Mr. Trump will withdraw again—and rightly so.

Using America’s money as an existential threat will rock the U.N. system. While many other reforms are possible, they won’t match the power of unilaterally controlling our contributions. Besides, we need a much larger defense budget; reducing contributions to the U.N. is a good start to find the necessary funding.

This article was first published in the Wall Street Journal on December 26, 2024. Click here to read the original article.