The former National Security Advisor in the Trump Administration and ambassador to the UN under George W. Bush inaugurated the FAES 2024 Campus yesterday. Just a few metres from Madrid’s Retiro Park, the veteran foreign policy expert spoke to EL MUNDO about international news, full of “threats”.

This article was first published in Spanish in El Mundo on September 24, 2024. Click here to read the original article.

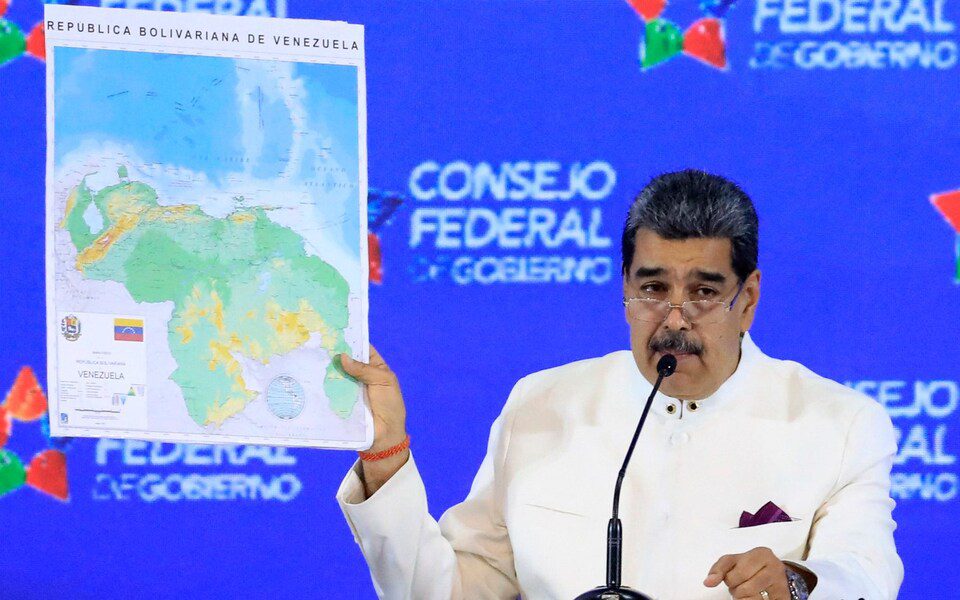

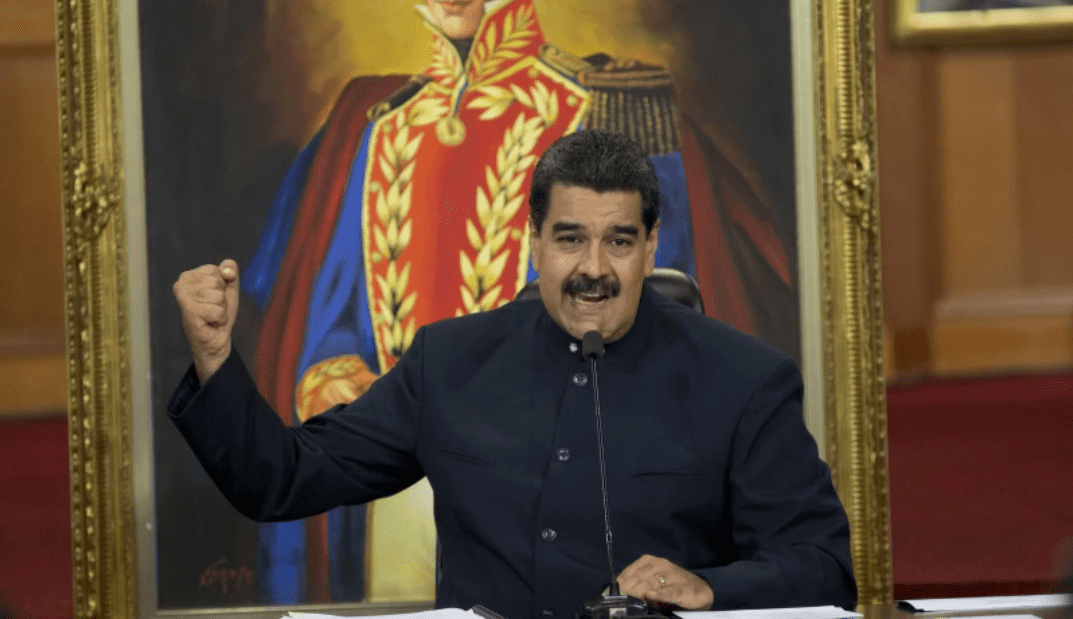

Question: You say that your biggest failure as National Security Advisor to Donald Trump was “not being able to help the people of Venezuela against the dictatorship of Nicolás Maduro.”

Answer: I feel that way. True. The conditions in Venezuela are so bad economically and politically that, from a strategic point of view, Maduro could not stay in power if it were not for the support of Russia and Cuba, as well as the intervention of China and Iran. So we have a global problem. We have the troika of tyranny, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba, plus other leftist governments in Latin America, which resemble a return to the 1950s and 1960s, again, which is strategically a problem for the United States, but at the same time it is terrible for the people of the American continent.

Q. How do you assess the latest events in Venezuela, with the Spanish government at the epicentre of the exile of the winner of the elections, Edmundo González?

A. Yes. Well… Maria Corina Machado is still inside Venezuela, hiding. So she is still in danger, as are many other opposition leaders. It was a mistake to agree to let Maduro hold elections. He was never going to allow freedom. Maduro began excluding Machado, even from running. And the votes that the electoral officials proclaimed were completely fictitious. It was an exact repeat of the 2019 elections. It was the same thing again. Maduro is doing the same thing.

over and over again. The Biden Administration is completely blind. Sanctions were lifted for a while. Now they have to be reimposed. But the damage is already done. (The) international coalition against the regime has deteriorated and it will be difficult to rebuild it. We don’t know who will win in November in the United States, but Donald Trump has already said recently that Caracas is one of the safest places you can go; that it is safer than many cities in the United States.

Maduro is obviously a strong man for Trump. I remember from my days with him that I was fascinated by the strong man and I don’t know if you’ve read the chapter on Venezuela in my book [The Room Where It Happened], but in the end we managed to get Trump, much to the chagrin of some, not to meet with Maduro. We didn’t let it happen. However, now, it is possible that Trump will make a deal with him. That would be a big setback.

Q: So do you think it is better for Venezuelans if Kamala Harris wins the November 5 election?

A: Well, I don’t think we know anything about her position on Latin America. The best prediction I can make is that, during the first year of a Harris Administration, she will follow the trajectory of the Biden Administration, because that’s what she’s been sitting in National Security Council meetings for for three and a half years.

Q: You say you will not vote for Donald Trump, but neither will you vote for Kamala Harris, and in the 2020 elections you announced that you were going to write Ronald Reagan on the ballot.

A: I thought about writing Ronald Reagan in 2020, but then I also thought that people might think it was too much even for a protest vote. So I wrote in Dick Cheney. Because I wanted to vote for a conservative Republican and there wasn’t one on the ballot. Trump has no philosophy [of government]. He doesn’t think in political terms like most political leaders. Think in terms of what benefits Donald Trump. So what he does in a second term is much harder to predict than people think because the circumstances are different.

Q. And what decision can you take with NATO? You are very pessimistic on this issue…

A. Yes, I think Trump can withdraw the US from NATO. He was very close to leaving. And we’ll see what happens in Ukraine between now and the election and, if Trump wins, between the election and Inauguration Day. I’m very worried. I’m worried that if Trump wins, Putin can call him the day after the election and say, ‘Congratulations, Donald, I’m very glad you were elected. The Biden administration has been a disaster. Why don’t we just get together and resolve all our problems? ‘ And Trump can easily say, ‘As soon as I’m inaugurated, you’ll be the first person I meet with.’

Q. That would be a serious problem for Europe…

A. A Trump Administration doesn’t understand alliances. It’s not just with NATO; Trump doesn’t understand the alliance with Japan; he doesn’t understand the alliance with South Korea… One of the first fights he got into as president was with one of our two closest allies: Australia.

Q. And what about the European position on the Middle East, sometimes so distant, as in the case of the Spanish Government, from the United States’ staunch defense of Israel?

A. It’s hard for most Americans to understand. Support for Israel is overwhelmingly strong among both Democrats and Republicans, although there are many Democrats on the left of the party who take a more pro-Palestinian stance: on college campuses, among American Muslim communities, and on the radical left of the Democratic Party; which is important. I think Europe is making a big mistake. He is buying into the propaganda about who is responsible for the Gaza tragedy. Obviously it is Hamas. If Hamas had not taken billions of dollars to build its underground fortress, that money could have been used for economic development, for the citizens of Gaza, and yet they did not benefit from it at all. Absolutely it is barbaric and cynical the way Hamas is using the Palestinian people to protect itself, and that all this is done at the behest of Iran.

Q. Your tough stance towards Tehran is unwavering…

A. The Tehran regime is the main threat to peace and security in the Middle East and I think, unfortunately, that until that regime is gone and the Iranian people have the opportunity to take control of their own government, there will be no peace and security, because in the meantime it is using a network of terrorist groups. We don’t know what will happen in Lebanon with Hezbollah, but the Israelis live in fear of it. Hezbollah has a missile capacity that can overwhelm Israeli defenses if thousands of missiles are put into the air at once. No air defense system can withstand it. Israeli population centers are very vulnerable.

Q. Your support for Israel is tenacious, but is it also for Benjamin Netanyahu and the war he is waging?

A. Netanyahu has become strong within Israel and I believe that the vast majority of Israelis really want him to eliminate the terrorists. I support the right to self-defense, which includes eliminating your opponent, and Hamas is an opponent, Hezbollah is an opponent. People say, ‘Can’t the war in Gaza end?’ The answer is yes: Hamas could surrender.

Q. What role does China play for you in the complex geopolitical landscape? In Europe, for example, there is still a desire to maintain a bridge with Beijing.

A. Europe has become very dependent on the Chinese market. This is a significant

difference from the Cold War, when Russia had almost no economic connection with Europe or the United States. But the Chinese use this economic connection to in their own interest and people should take that into account. In the United States, companies are not making new capital investments in China. They are looking for alternatives. South Koreans are not investing their money in China either.

The place that is out of date is Europe. And that puts Europe at greater risk. It has also been difficult to convince European governments. Companies like ZTE and Huawei are a threat, and they are not just telecoms companies, they are arms of the Chinese state, designed to take over fifth- generation telecommunications so they can get all the information they want. This is unprecedented in history: using commercial companies in this way, as intelligence arms.

Q. Are we Europeans then naive?

A. Everyone has misjudged China. The US didn’t fully appreciate the threat from Huawei and ZTE until the Australians and New Zealanders sounded the alarm, explained it to us, and fortunately we realised they were right. We then went to the British and told them our whole intelligence-sharing relationship could be in jeopardy. They didn’t believe us, although they do now. Then we tried to talk to the Europeans, on the continent, where we’re having mixed success.

Q. And yet Europe must fear the Chinese connection with Russia…

A. Like South Koreans, the Japanese, and the Taiwanese… who are seeing that same connection between China and Russia.

Q. What do you think of the peace plan that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is about to present?

A. Zelensky hopes to demonstrate with his peace plan that Ukraine is flexible.

But he may be making a mistake in trying to be too reasonable, because Putin is not going to be.

Q. This week the United Nations General Assembly is being held in New York and you are the author of the famous phrase…

A: ‘if the UN headquarters in New York lost 10 floors today, no one would notice.’

Q. That’s it. Do you really think it’s not worth it? Will what is happening and discussed these days in New York mean anything?

A. The United Nations is a large and complex organization, and that is part of its problem. But several of its specialized agencies do very important work: the International Atomic Energy Agency, the International Telecommunication Union, the International Maritime Organization,

the World Health Organization (WHO)… They all do a good job when they are not politicized, and in the case of the WHO, for example, we could see how Chinese influence and politicization affected them during Covid. The problem with the UN is that its political decision-making bodies are paralyzed and irrelevant. The General Assembly does almost nothing. And the Security Council is broken by vetoes from Russia and China. The real reason the UN was created was political. It was the answer to the failed League of Nations. It was supposed to stop World War III, but the fact that we haven’t had a World War III has had nothing to do with the United Nations. It’s had to do with the West prevailing in the Cold War. Now it’s going to stop World War III.

We are going to have… I don’t like to call it a second Cold War… it is a very different circumstance… it is a Sino-Russian axis that is a reality. So in the Security Council we are going to have the United Kingdom, France and the United States on one side, and China and Russia on the other.

Q. Let’s end with the future of the Republican Party to which you have dedicated so many years of work since you were in the Reagan Administration. What awaits the political party whether Donald Trump wins or loses?

R. A fight is going to break out in the Republican Party whether Trump wins or not. Let’s say he loses… As I said, Donald Trump has no philosophy, he doesn’t do politics, there is nothing he can pass on to his successors, apart from his style and his way of acting, which is a performing art. So there is no Trumpism. Because Trumpism is what he decides on a given day. After this fight, the Republican Party can return to a Ronald Reagan style, to that kind of party in a few years. If Trump wins, the fight will be greater, because he will be in the White House. But it must be remembered that Donald Trump will become a lame duck the very day he is sworn in, since he will not be able to run for president of the United States again. And that is a very different circumstance than the one he faced in his first term, where he had an eight-year runway.

Potentially, you now only have a fixed term of four years, which goes by very quickly.

This article was first published in El Mundo on September 24, 2024. Click here to read the original article.