By Dr. David Wurmser

April 6, 2021

The value of elections is not just that they produce a winner and loser in determining who runs the nation. Elections are also diagnostic tools ascertaining societal trends and ideas. While Israel has been deadlocked in stalemate with almost no movement in terms of delivering a winner and loser in the last four elections cycles, those cycles have nevertheless with clarity and richness exposed tremendous effervescence and movement in Israeli society.

On winners and losers

In terms of deciding who will rule Israel in the coming four years, each round of elections has resulted in deadlock. However, in terms of how the two blocs are defined, and around what set of questions coalitions are to be formed, the nature of the two blocs has changed. The first campaign in 2018 was defined around traditional security, economic and social questions. The previous government had collapsed over its handling of inconclusive fighting in Gaza, and the public debate was in part dominated by this question, especially within the inter-right debates. Only two years later, in the fourth round of elections just concluded, all these questions were almost entirely absent. Blocs divided up almost to the complete exclusion of all substantive issues around the question of whether Netanyahu should, or could, be reelected. There was almost no mention of Gaza, of COVID-19, of Iran, of the new Biden administration, or any other issue of gravity. This election was almost entirely a personal verdict on Netanyahu. Even the election returns graphics on the news on election night divided the columns of parliamentary seats between the “camp against Netanyahu” or “camp to replace Netanyahu” versus the “Netanyahu camp.”

Ironically, the ones who have had the greatest confidence that Netanyahu can continue to lead the conservative camp in Israel are actually the traditional leftist leadership that started the “rak Lo Bibi” (“Anyone but Bibi” — Netanyahu’s nickname) movement. One of the central assumptions of the “Anyone but Bibi” campaign was that Netanyahu represents the center of gravity, the indispensable pillar, for the right. He was the standard bearer for slow erosion of power of the left, and thus personally represented the greatest threat to that establishment. His removal, thus, is seen by this camp on the left as a sine qua non of breaking the iron grip the right has had on Israeli national politics for most of the last three, or even five, decades.

And yet, the left simply could not muster the numbers to break that grip. The elections of 2015 involved the considerable intervention of the U.S. under the Obama administration in money and operatives. Still, it failed to tear Netanyahu down. Indeed, it was the final highwater mark of the left although it was not a high enough mark to succeed.

As such, in its attempt to tear Netanyahu down, the left realized that it would have to find allies on the right whose aspirations ran up against the ceiling of Netanyahu’s continued tenure. The maneuver for these strategists on the left is to convince those on the conservative side that Netanyahu is too politically weak or morally tainted to lead the right while at the same time to pursue a strategy which in contrast emanates from frustrating confidence the left holds in Netanyahu’s ability to lead the right. This is tension — which externally portrays Netanyahu as an albatross while internally believing he remains the irreducible pillar of the right — cannot be long maintained.

But this may be one of those times of where one must be careful of what one wishes, for it may come true. The recent additions to the “Anyone but Bibi” camp are reading the sentiments of their own more right-leaning constituents. They are not listening to arguments from the left about Bibi’s being an albatross, and they do not believe they need the left as an ally. They believe that about two years ago – around 2019 – Netanyahu reached the tipping point from being an asset for the right to being a drain. Namely that while he retains a strong following in a good section of the right side of the spectrum, he is no longer able to deliver for the right the full spectrum of votes he needs to stand up a government, and even if he does, he is increasingly embarking on policies of political survival, maneuver and navigation rather than seize the moment – especially following the 2014 war with Hamas and under the Trump administration to fundamentally alter the underlying strategic reality. In other words, while there remains deep appreciation for Netanyahu’s historical achievements in the economy, and in his tactical skill in navigating the hostile Obama administration, there is disappointment that he did not capitalize strategically more aggressively during the Trump years. Settlement was tepid, absorption under Israeli law of areas has followed America’s lead and has not been followed up with actions on the ground, Hamas remains a constant problem and sets the agenda on the border of Gaza, and Iran is obstructed but not defeated – the IDF is still defensive. As such, there is frustration on the right not only that he cannot deliver a government in the last two years but that even before that, he was operating tactically rather than strategically to change the terms of debate in favor of the right, on defense, social and foreign policy issues.

The evidence this community of right-leaning politicians highlights to support this electoral and strategic outlook is that the right side of the Israeli spectrum – defined around party positions on both security and social issues — has been inexorably growing for years. And based on examining the platforms of the left-leaning parties, some of them, as well, seem to be drifting away from many of the hard-charging leftist positions of the past. In short, not only has the right-bloc portion within the spectrum continued to grow, but the whole spectrum has shifted altogether. There is thus a growing community on the right that argues the inability of the right to translate the electoral shift to the right with a solid right-wing governing coalition is attributable personally to the lingering presence of Netanyahu as the camp’s leadership.

Beneath all the sound and fury, thus, there seems to be a consensus that the balance of the Israeli electorate is not only to the right but is moving more so in that direction. The left, however, believes that it is because Netanyahu continues to be the insurmountably capable politician whom they cannot overcome, while a community on the right believes it is despite Netanyahu’s being an albatross weighing them down both electorally and strategically.

Prime Minister Netanyahu and his supporters essentially agree with the left camp on his role. They continue to see him as the standard bearer of the right who, if toppled, will reverse the political tides and allow for a resurrection of the left. In particular, this camp sees the attack on Netanyahu to be a manifestation of the overall attack of the elites and founding “Mayflower” generation on the panoply of communities largely ignored and underrepresented since Israel’s creation by a socialist, secular European (particularly Russian and Polish) establishment. These communities – later immigrants, liberal-nationalists, settlers, religious, religious-nationalist, oriental Jews, non-socialists (including recent Russian immigrants) – found an unlikely home under the archetypical Polish Jew, Prime Minister Menahem Begin, and his Likud Party in 1977, and they have never parted ways since. Prime Minister Begin was the epitome of the anti-establishment, his identity was deeply traditionally Jewish, not secular-socialist, and he was thus their leader. So these “outsider” communities — especially those for whom traditionally respect or adherence to Judaism, or for whom a more “Jewish” rather than “Israeli” sense of identity mattered such as the religious, religious-nationalist, recently-immigrated and the Sephardi Jews — the epically Polish Begin was their salvation. These followers still clearly form the critical mass of the right. For them, the attack on Netanyahu is just the latest rendition of the establishment nemesis they had faced all along, and any surrender to the assault on him would be tantamount to surrendering their effort to demand enfranchisement and respect.

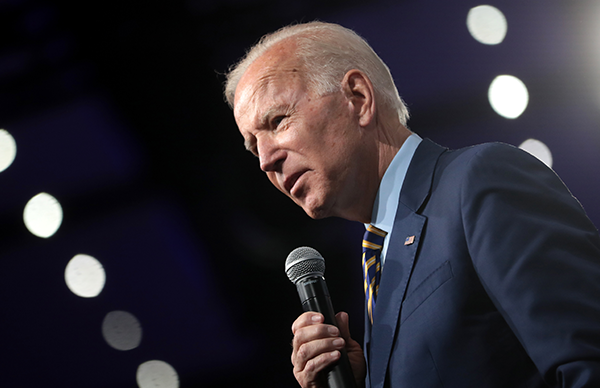

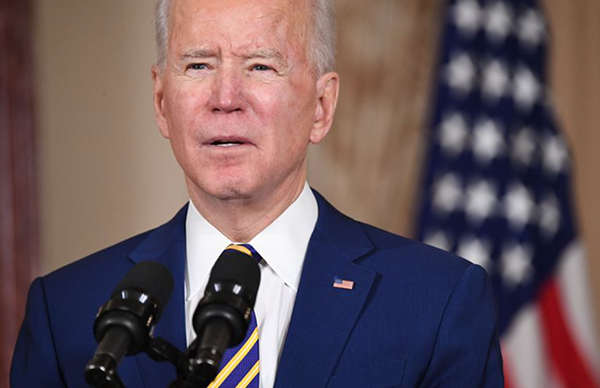

A broader community of support for Netanyahu also includes those who feel the economic, security and social stresses and challenges Israel faces going forward – especially rehabilitating the economy after COVID-19, dealing with Iran growing as an acute threat, and navigating the Biden administration as it takes office with an anticipated distancing from Israel. All these challenges demand a seasoned, proven leader. Netanyahu’s many years in office and his generally acknowledged success stand in contrast to the complete absence of executive experience of his opponents.

Important shifts underneath the deadlock

The numbers in each round of elections – which reflect impressive stability in terms of the question of anointing a new leader – also reflect that the left camp continues its slow decline. Its votes seem to be bleeding to the right-camp’s community of Netanyahu skeptics. The right camp that supports Netanyahu seems to be slightly changing its internal composition but has remained rather consistently hovering around 59 seats. A flashing warning sign for Netanyahu, is that the Likud lost a lot of ground in core communities, such as Dimona, Beer Sheva, Jerusalem and Bet Shemesh. Additionally, Naftali Bennett’s Yemina (Rightward) party – which is wavering between the pro-Netanyahu and anti-Netanyahu camp on the right – and grew considerably, signaling that the unquestioned support for Netanyahu is beginning to seriously wobble even if it still holds to some extent. Essentially, Yemina voters knew they were voting for Netanyahu as prime minister indirectly (since Bennett signaled before the voting began that he would align with Netanyahu), but had taken the first stride on the psychological bridge away from Netanyahu by voting for Bennett. This trend shows every sign of accelerating in the next months.

While still needing a magnifying glass to discern, there was a highly significant shift in the recent election in the Arab community – part of it began voting as the latest “outsider” group finding a home in Likud against the establishment they see failing them. While one should withhold long-term judgment on whether this continues, voting in the Arab sector for Likud grew between four and ten-fold (for example, from 1% to 4% in partly Christian Nazareth, and from a half percent to 6 percent in all-Muslim Rahat). The Arab community understands it is in crisis, that it needs the help of the state, and that its traditional allies in the Jewish establishment have proven useless. These establishment parties’ leaders appeared to ever more Arabs as focusing more on theoretical expressions and demonstrations of Arab rights than in pursuing practical policies which allowed them to realize their rights.

More dramatic was the transformation of one of the main Arab parties, Raam (Reshima Aravit Meuhedet – the United Arab List) under Abbas Mansour. Originally an Islamist, Mansour sensed this shift in the Arab community and campaigned on participating in Israeli government – all other Arab parties had focused on using their parliamentary power as a platform to stage a display of support for national identity and rights – and inviting the Israeli state into their community to address the rising list of severe problems afflicting it. In the course of the campaign, Mansour developed a close relationship with a key Likud strategist and Netanyahu ally, Yaron Levine, laying the groundwork for a potential earthquake: a Likud governing coalition building a majority on an Arab party. While the success of standing this coalition up may still be unlikely, it does show the Arab community is the latest “outsider” community that rejects its establishment leadership and seeks an entry ticket into the heart of Israeli politics, and sees the “outsider” Likud as the path, or ally, to get there. Social issues, and communal interests emanating from those social issues, are beginning to define coalitions and alliances. The Raam party is on the more traditional side of the Arab political spectrum, with an Islamist pedigree. And yet, it sees the threat represented by socialism and secularism to be great enough to drive them into alliance with more traditional Jewish parties.

Indeed, the low Arab voter turnout and the drift, however limited, away from the parties for which the Arab community have traditionally voted, toward the “outsider” Arab party and even the “outsider” Jewish party, such as Likud, reveals a deep frustration among Arabs with the traditional societal and political leadership. More Arabs voted for Likud (21,500) than for Meretz (15,000), which focused its campaign heavily on equal rights for Arabs, and Yesh Atid (8,000), which is that standard-bearer party for the left. Another right-leaning party, the anti-Netanyahu Avigdor Liberman’s Israel Our Home party also gain about 13,000 votes – nearly as many as Meretz. In earlier rounds, as many as 35,000 had voted for Meretz, and at one point long ago up to 150,000 for the Labor party, while Likud measured imperceptibly. As far as Arab parties go, the Joint List Party led by Ayman Oudeh – essentially the “establishment” party of the Arab community, got 207,000 votes (6 seats) as opposed to its high water mark in 2015 with two and a half times that number. The Arab establishment and the aligned Jewish left-leaning establishment are both losing the following of the Arab community.

Another relatively subtle, but potentially significant shift appearing in these elections was in the Haredi (Ultra-Orthodox Jewish) community. There has been a growing frustration with the stagnant leadership of the Haredi community, especially the European (Ashkenazi) Haredi community – in contrast to the Oriental (Sephardi) community which tends to be more flexible – among the community’s youth. Specifically, there is a palpable desire among the youth to participate in Israeli life as Israelis, rather than continue their rarified, separated life in the Haredi “ghettos” in Israel where they were strongly discouraged, and at times prevented, from serving in the Israeli army, which is generally a pathway to participation in Jewish Israeli life. A sign of the change had already come through language: Haredi youth increasingly spoke Hebrew, not Yiddish.

This trend among Haredi youth led to a shift in this election from voting for the Haredi leadership to voting for a right-wing religious-nationalist party, the Religious-Zionist party under Bezalel Smotrich, which accounts for that party’s unexpected success, let alone its survival (it had been expected to fail to cross the electoral threshold). This shift was quite evident in voting patterns in bastions of Haredi support, such as in Jerusalem, Bnei Brak and Bet Shemesh. About 25,000 votes were taken away from United Torah Judaism (UTJ), the Ashkenazi Haredi party and the larger Shas, the Sephardi Haredi party, lost 37,000 votes. The leader of the UTJ was so angry about the drift of youth from his community toward the religious-nationalist camp that he refused over the last week to commit to a government led by Likud that included the religious nationalists. He certainly will join any government under Netanyahu, and its leader, Moshe Gaffney, even says so, but his formal balking for a few days is symbolically meant as an overt demonstration of pique and protest.

Finally, the elections highlighted another trend. The path to top political leadership in the past, especially from the 1970s onward, led through being a general in the IDF earlier in one’s career. Even after the period in which the Likud started dominating the scene, the effort to reverse the tide against the left was almost always led by a general. Because of the restrictive ways in which the Labor party, which ran the state and all its affiliated institutions, monopolistically until 1977, almost all former generals were affiliated with the Labor party movement. Thus, the security elites until recently were almost entirely secular, socialist, and European Jews. Since the right campaigned on the issue of security, especially in the wake of the disastrous Oslo Accords in 1993, the left saw it as its best strategy to try to turn the tide against Likud by handing a former general their standard. In essence, by bedecking themselves with a mantle of generals, the left banked on the reputation of the IDF in Israeli society to parry Likud’s accusations of their being soft on security. Ehud Barak was the highwater mark of this effort, although he managed to become prime minister for only a short time. The final effort in this regard was the rise of the Blue-White party of the last three years, led by three generals – Benny Gantz, Gabi Ashkenazi and Moshe Yaalon. Moreover, going forward, more and more of the retiring senior officers are themselves from the “second Israel,” namely, the communities that were largely unrepresented in elite institutions prior to 1977.

Not only did the left finally abandon this formula in the last round of the elections and turn instead to a “split the right” strategy – since the Blue-White “generals” effort had failed to deliver – but the shift in the Knesset away from former generals toward settlers continued. This Knesset election returned fewer former generals (only six – Gantz from Blue-White, Yair Golan from Meretz, Yoav Galant and Miri Regev from Likud, and Orna Barbibai and Elazar Stern from Yesh Atid) and more “settlers” (18 from the Jerusalem area and 7 from Judean and Samarian settlements). And to note, a third of the generals in Knesset now are themselves from the right-bloc parties.

Conclusion

The recent round of national elections in Israel failed to produce a winner, and instead delivered the fourth deadlock in two years. The current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who fell short of a majority in terms of his natural coalition, now has a narrow, if not unlikely, path to a narrow right coalition with some untraditional allies. The left has almost no path at all since too many of the anti-Netanyahu block are themselves on the right side of the political spectrum. They agree in opposing Netanyahu, but nothing else around which an opposition-based government could be formed.

This deadlock raises the specter of a fifth election cycle two years, the third in 18 months. The gradual decline of the left, and the failure of the Netanyahu bloc to finally cross the 61-vote threshold, however, suggests pressure to avoid a fifth round. For the left, each cycle returns a slightly more right-leaning parliament. For Netanyahu, the bump he enjoyed driven by the Abraham Accords peace treaty, the masterful handling of the COVID-19 crisis, and several other substantial successes in the last months still failed to deliver victory. It would not be easier in a fifth-round, and if no new government is installed by November, opposition leader Benny Gantz would assume office and become the incumbent as a result of the rotation agreement Netanyahu and Gantz signed last year to form the caretaker national unity government currently governing Israel. In other words, time works against, not for, PM Netanyahu.

And yet, despite this deadlock, the underlying trends revealed by this round of elections suggest that Israeli politics are actually entering a period of great, if not bewildering, change.