A full withdrawal from Afghanistan is a costly blunder and failure of leadership.

This article appeared in Foreign Policy on April 19, 2021. Click here to view the original article.

By John Bolton

April 19, 2021

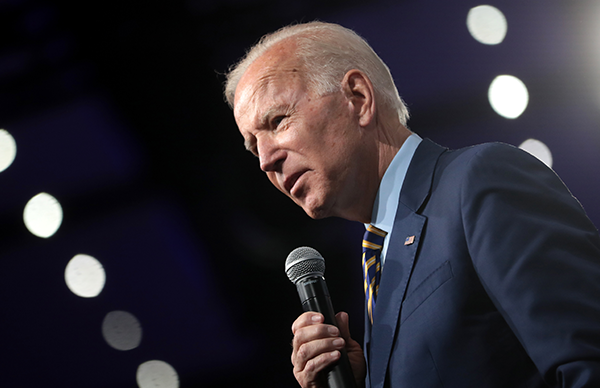

U.S. President Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw the United States’ remaining military forces from Afghanistan rests far more on domestic politics than on national security strategy. In 2020, he campaigned on the issue. He said last week, “It’s time to end the forever war.” We should “be focused on the reason we went in the first place: to ensure Afghanistan would not be used as a base from which to attack our homeland again. We did that. We accomplished that objective.”

Biden sounds like his predecessor, Donald Trump, whom I served as national security advisor. That’s no surprise, as Biden is carrying out Trump’s policy with only slight modifications. Media coverage of Biden’s April 14 announcement has noted widespread public support for bringing the troops home. The American people are tired of foreign military engagements, or so the pundits tell us; they’re tired of Afghanistan, tired of Iraq, tired of Syria, tired of terrorism, tired of the Middle East—just plain tired. The chattering classes agree, academics agree, Democrats almost unanimously agree, and even some Republicans agree.

They are all wrong.

The basic national security goal that all U.S. leaders must pursue is to define their country’s strategic interests and how to protect them. Politicians must then justify how they propose to defend the country against external threats and to muster the necessary resources. When leaders do not explain hard realities, the public’s resolve flags, which politicians then use to justify their own hesitancy to make hard decisions. In effect, weak politicians switch cause for effect, levying responsibility on the people instead of themselves. Under Trump and former President Barack Obama, and now perhaps Biden, it wasn’t the public that was weak but its leaders, who were unwilling or unable to do their job.

Afghanistan proves the point. If the Taliban return to power in all or most of the country, the almost universal view in Washington today is the near certainty that al Qaeda, the Islamic State, and others will resume using Afghanistan as a base of operations. On April 14, Biden said that terrorism had evolved since the 2001 assault on the Taliban and that “the threat has become more dispersed, metastasizing around the globe.” Of course it has. That’s because the United States and its NATO allies have substantially denied al Qaeda its preferred safe haven for 20 years. Terrorists had to go elsewhere, seeking Middle Eastern or African zones of anarchy, because they had no choice. But make no mistake: Afghanistan, more remote particularly from the United States, is their preferred staging ground.

Washington didn’t create the threats, and the withdrawal won’t make them disappear.

In Biden’s own words, the United States obviously cannot “ensure” that terrorists will not again use a Taliban-dominated Afghanistan as a base to strike the U.S. homeland. Biden recognizes this danger by saying the United States will maintain “our counterterrorism capabilities and the substantial assets in the region” to guard against a future strike. Blunt geography, however, shows Biden is wrong to think that the United States can have comparably effective counterterrorism and intelligence-gathering assets after departing Afghanistan. After all, Osama bin Laden settled there after being expelled from other countries precisely because its remoteness made it attractive. The map hasn’t changed.

And what exactly is the United States doing today in Afghanistan? To the proponents of withdrawal, it has been 20 years of endless, daily, bloody combat. But this narrative is false, especially during the last seven years following the transition of NATO’s International Security Assistance Force into Operation Resolute Support. Afghanistan remains extraordinarily dangerous, and there have been casualties, but the last U.S. combat death occurred in February 2020. Moreover, there is no proof of real financial savings from withdrawing the approximately 3,500 remaining U.S. military personnel; the costs for Washington may well increase after the withdrawal because of the greater distances that must be overcome for any future operations.

Moreover, U.S. allies are performing a key mission in Afghanistan: training, advising, and assisting the Afghan National Army and other security forces. This is not combat. The roughly 10,000 troops from NATO members and nonmembers deployed as part of Resolute Support are a much-reduced presence from the International Security Assistance Force’s peak of 130,000. Their departure alongside that of U.S. troops is a severe blow to a free Afghanistan.

Concededly, the United States has spent enormous sums on so-called nation-building activities in Afghanistan, with precious little to show for it. It never should have been the United States’ objective to create a Central Asian Switzerland, even if it had the ability to do so, which it does not. But it is an even graver mistake to conclude that because Washington wasted resources on the wrong objective before, withdrawal is now justified. The United States hasn’t engaged in nation-building for many years and has long moved beyond these costly mistakes.

Supporters of withdrawal assert that the United States has tried long enough to enable the Afghans to defend themselves and that U.S. responsibilities are over. Those making this argument miss the key point that it is U.S. security that is at stake, not Afghan military competence. Washington and its allies are not there to protect Afghans against Taliban solely for their sake but to protect against the terrorist threat to Western nations that has previously emanated from the petri dish of Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, and would do so again.

To that end, the United States concentrates on gathering information on possible terrorist threats through a variety of mechanisms, not just the military. It is, however, the military presence and a considerable logistical base that enable much of this critical work. And it is in-country U.S. armed forces, which can scale up rapidly, that provide confidence that no sustained terrorist threat can reemerge while the United States remains. Removing the troops removes a key predicate.

Biden, having in effect tacitly admitted that the United States has not achieved its basic objective of safeguarding the homeland, then complains that new objectives have been established. That is true; reality has changed since the initial victory over the Taliban and al Qaeda. But it is hardly a radical departure for the United States to remain overseas for long periods when it has substantial interests there, even if those interests change dramatically. Biden is quick to say he is restoring U.S. leadership in NATO—yet there have been no complaints that the United States has had troops garrisoned in Germany for over 75 years since destroying the Third Reich. The same goes for Japan and South Korea. With U.S. troops remaining in those places, Trump could say that Biden is not following their shared rhetoric to end “forever wars.”

Long-term deployments in dangerous places can be required by long-term threats to the United States. Washington didn’t create the threats, and the withdrawal won’t make them disappear. The war against terrorism is unlike 19th-century conventional warfare not because the United States made it so but because the terrorists did. Even conventional warfare is changing, as we are seeing in cyberspace and the varieties of asymmetric and hybrid warfare being developed and deployed by adversaries hoping to leverage their smaller strengths against Western weaknesses. The war against terrorism is open-ended in the same way the struggle against international communism was open-ended. Many of the same people who disliked having to defend the United States in the Cold War—and their ideological successors—dislike having to defend the country against terrorism. Too bad the United States’ enemies won’t give it a break.

Among other reasons to stay in Afghanistan is keeping watch on the risks emanating from Iran and Pakistan. These are clear cases where geographic proximity has no substitute. Iran’s continuing nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs; its unwavering support for terrorist groups such as the Houthis, Hamas, and Hezbollah; and its belligerent conventional military activity around the Middle East all mark it as an aspiring regional hegemon whose near neighbors have become increasingly anxious. Afghanistan is an excellent, proximate location to keep an eye on things inside Iran. Moreover, a Taliban takeover, which could lead to a distinctly fragmented pattern of Afghan government, would undoubtedly increase Iran’s influence in western Afghanistan as before, to the United States’ distinct disadvantage.

Perhaps Biden is turning into a modern-day George McGovern, the Vietnam-era Democratic presidential nominee who made “come home, America” his mantra.

A U.S. withdrawal may be even riskier with respect to Pakistan. If the Taliban resume control in Kabul, this can only encourage the Pakistani Taliban and other Islamist radicals, including within the Pakistani intelligence services. Since Partition in 1947, Pakistan has never had a reliably stable government. Instead, to paraphrase the famous jibe against Prussia: Where some states have an army, the Pakistan Army has a state. If Islamabad’s government fell to the radicals, terrorists would possess a significant number of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, not only threatening India and others but also risking the proliferation of nuclear weapons to terrorists worldwide. For Washington, this is perhaps the most dangerous consequence of the Taliban retaking power in Afghanistan, yet it rarely receives significant attention.

Moreover, ignoring the follow-on effects of a U.S. Afghanistan withdrawal on Iran and Pakistan does not augur well for Biden administration’s national security policies globally. The United States’ continuing and probably growing strategic struggle with China and Russia, the critical need to prevent the further accumulation of weapons of mass destruction by North Korea and Iran, and the threat of proliferation more broadly should be matters of enormous concern. Weakness and self-congratulation are often contagious.

Recently, media commentators have breathlessly proclaimed that Biden is governing much further to the left in domestic affairs than most people predicted. Perhaps the same is coming true in the international arena—and Biden is turning into a modern-day George McGovern, the Vietnam-era Democratic presidential nominee who made “come home, America” his mantra. Unfortunately, that call is a dream, not a strategy. It is not a dream that ends well.